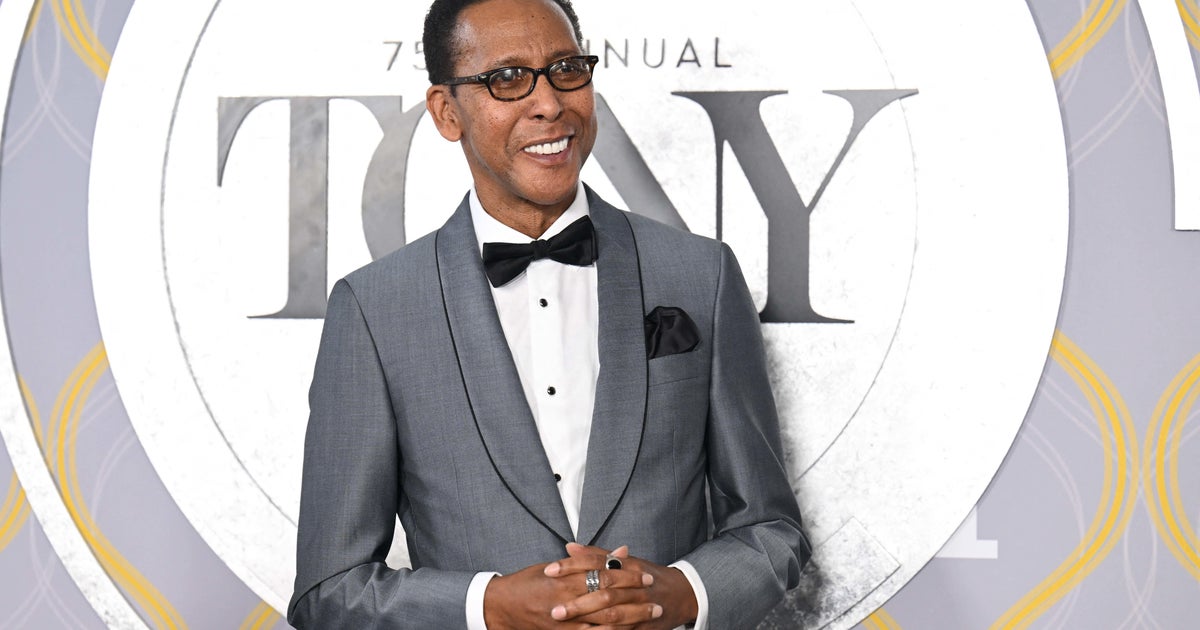

Gluck’s 1762 interpretation pares the tale down to just a trio of voices and chorus, and this current cast works wonders: Countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo sings the noble Orfeo, soprano Ying Fang sings the recently deceased Eurydice and soprano Elena Villalón makes her Met debut as the cheeky Cupid Amore.

Costanzo, who is onstage and singing for the entirety of the opera’s uninterrupted three acts, brought to Orfeo a beautiful balance of mythic transparency, heroic humanity and intriguing mystery — he’s rendered here as a man in black with a guitar and silver spangled shoulders. (The countertenor David Daniels was the first man to sing the role at the Met for the premiere of the current production in 2007; subsequent revivals have cast mezzos like Stephanie Blythe and Jamie Barton.)

His mourning effectively echoed “the voice of the wood dove” through the first act, grieving with soft attack over the little black box of Euridice’s grave. And while there was some shaky footing in Costanzo’s introductory “Ah! se intorno a quest’uma funesta,” his voice swiftly sturdied, locking into a firm embrace with the orchestra. His song in the Elysian fields (“Che puro ciel”) was jewel-clear and soaring. And by the time we reached the demanding Act III aria — “Che faro senza Eurydice?” — his tone was bright and gleaming — his one or two faltered notes promptly forgiven by a long and long-delayed ovation.

The rich, rounded voice of Chinese soprano Ying Fang made a lovely foil to the blade of Costanzo’s countertenor — a lovely soft-hard timbral fit that formed the tight braid of their third-act duet (“Vieni, appaga il tuo consorte”/”Viens, suis un époux”). She’s also a fine actress, with remarkable expressive range. I loved listening to her anguish between life and the “peaceful oblivion” of death in the final act. (However unfairly, she makes a fair point: If Orf can’t even look at her, why bother resurrecting?)

Elena Villalón was the surprise treat of the night as Amore, who descends from on high in a T-shirt, khakis, sneakers and a pair of store-bought wings. She brought a big, wide, golden voice and surplus charm to the proceedings, with a sensational “Gli sguardi trattieni Amor” in Act I. Villalón also lit up Act III’s happy (and pleasantly hammy) ending.

Costanzo’s true counterpart in this love story is the chorus, which presides over the action from its station in the stands. Its 86 singers are a gallery of the dead: Among their ranks are kings, queens, nuns, nursemaids, Edwardian gentlemen, Victorian ladies, cowboys, baseball players. One could (and did) get very distracted scanning each for the suggestion of their stories. Vocally, I can’t recall this chorus sounding better — achieving misty lightness in Act I, appropriate fury in Act II and celebratory exuberance at the finale. (If you managed to see “Only an Octave Apart” — Costanzo’s 2022 cabaret with Justin Vivian Bond — the resounding interjections of “No!” from the chorus in “Deh placatevi con me” will inspire a smile.)

The pouncing strings of the overture didn’t give so much as a glimpse of the music to come (Gluck pinned it on to satisfy the ceremonial demands of the Austrian emperor’s name day), but did offer a forecast of conductor J. David Jackson’s energetic evening from the podium.

A last-minute replacement for Christian Curnyn (who fell ill), Jackson brought admirably sustained vigor to Gluck’s score, moving things right along, attending the opera’s many dances with bright, bristly playing and brisk forward momentum — much of it driven by the harpsichord of Jonathan C. Kelly and the glimmering harp of Hannah Cope (a sound that belies how much heavy lifting it does in the score). I loved the darting violins and flourishes of oboe and flute that introduced the Elysian fields; and the triumphant throwdown of the finale has been stuck in my head since I left the hall.

The other star of this show is movement itself. Morris animates every inch of the opera — from the small gestures that cascade up the tiers of the chorus like leaves rising in an updraft to the whirling halo of dancers surrounding the grieving Orfeo. Bodies unfurl like banners, spin like tops, lock arms and cycle in circles. Gestures recur like musical themes: They sneak glances, they avert their gaze and cover their eyes, they crane their necks to the heavens, they sink to the floor.

The staging, too, indulged a sense of movement that yielded several spectacles — a seemingly endless stairway to the underworld descending from the rafters; a carousel stage revealing the unexpectedly detailed crags and tunnels of Hades; the hand-pushing parting of the choral stands, its imposing geometry catching harsh light.

Morris’s is a production that leaves plenty of room for everything you love about opera and refrains from extraneous massage of the material. The result is an underworld worth a visit — or two.

“Orfeo ed Eurydice” runs at the Metropolitan Opera through June 8, www.metopera.org.